This is the UN-edited article published in the July 2002 issue of Massage Magazine.Mid-Back Tension"Intention and Imagination"by Taum Sayers

One of the keys to success when using corrective massage includes utilizing intention and imagination. Rumor has it that humans utilize only a small percentage of our potential abilities. I believe we can increase that percentage when we exercise and thus support our ability to imagine, intend, and see outside the box. Portions of the following information serve to encourage the innate ability to listen to and utilize the clues your client's tissue is providing. My primary mentor, Lauren Berry Sr., RPT, and Structural Engineer, often described a successful therapist as part detective and part mechanic. It would appear that intuition and imagination aid both of these roles.

One of the primary goals of The Lauren Berry Method® of Corrective massage is to enhance the body's health by addressing its constant balancing act regarding its relationship to gravity. These techniques serve to reduce tension and nourish the body's innate repair mechanisms by encouraging the body to return to a state of balanced posture and ease. Practitioners never claim to "fix" anything but rather to reduce the obstacles that interfere with the body's incredible natural healing abilities.

This unique approach to relieving soft tissue tension also recognizes that the point of pain is often the result of regional or distant tension. We can apply a bit of creative visualization to understand this point with what I call my "nose-ring analogy." (see below) Imagine you have your nose ring in today. Now imagine there is a ten-foot-long chain attached to your nose ring. Now pretend someone on the other end of the chain pulling and applying a rather uncomfortable tension. Where is the pain? Most likely in your nose. What is the source of that pain? Obviously, from the tension exerted at the other end of the chain. Many pains throughout the body can be compared to this situation, for the point of most noticeable pain for your client is often the result of a distant tension.

A good foundation includes knowing your anatomy so that when a client points and says, "It hurts here", you can 'see' the pertinent muscles in your mind's eye and then tactilely follow along the length of the muscle attached near that point of tenderness and address the various tensions, adhesions, and distortions that might be contributing factors. This approach recognizes, respects, and addresses this situation throughout the body, often reducing pain and restoring function with remarkable speed.

Let's take a walk through several of the numerous considerations when I apply a portion of Lauren's "Body of Knowledge" to a very common concern, the tension between the shoulder blades.

In focusing on any of the common concerns among clients, there are numerous considerations to take into account. First, when there is trauma and stress to tissue, the surrounding tissue often goes into a protective mode and immobilizes to protect the area from further damage. This is similar to a cast on a broken arm. This natural 'casting' serves the useful purpose of allowing the body momentary protection from further injury so that it may adapt quickly, deal with the present situation, and begin the repair process. This appears to be part of the body's innate survival program.

While this protective adaptation initially serves its purpose well, it is similar to applying duct tape to mend a tear. A useful yet transitory solution, rarely efficient for long-term healthy function. Problems often arise when the tension (duct tape) remains long past the body's need for that protective mode. Therapists asked to work on long-standing concerns of their clients can often add to their success rate of pain reduction by respecting that we are often not so much addressing the initial problem as we are the body's historical adaptations and compensations.

The Rhomboids are not necessarily the culprits in Mid back tension.

The thoracic region often has a long history of protective contraction. Consider that each time our body has fallen, beginning with the first time we fell off our tricycle, we automatically stuck our arm out to protect our face from hitting the sidewalk. Someone may have bandaged the scrape on our hand or put a band-aid on our elbow, but it is a rare parent that thinks of massaging the area where some of the unseen shockwaves traveled up that arm and settled -- the upper back. Additionally, many of the actions and postures taken on with common daily routines have a tendency to stress this area. As an example of the body's ongoing balancing act, if you were to adopt an imbalanced posture, such as leaning over the sink to wash the dishes or brushing your teeth, your hamstrings and a variety of muscles throughout your back may go into minor contraction to keep you from falling forward into the sink.

Sure, humans can adapt to the various insults to our upper back, but not without an accumulative cost. In this case, the price is often an ongoing tension between the shoulder blades.

Let us address this situation using two techniques within this Lauren Berry Method® Practitioner's approach that work together rather well:

- Encouraging the muscle to relax; and

- Repositioning misplaced tissue.

This article will focus specifically on several of the muscles often associated with tension in the thoracic area, the Iliocostalis Thoracis and Iliocostalis Lumborum.

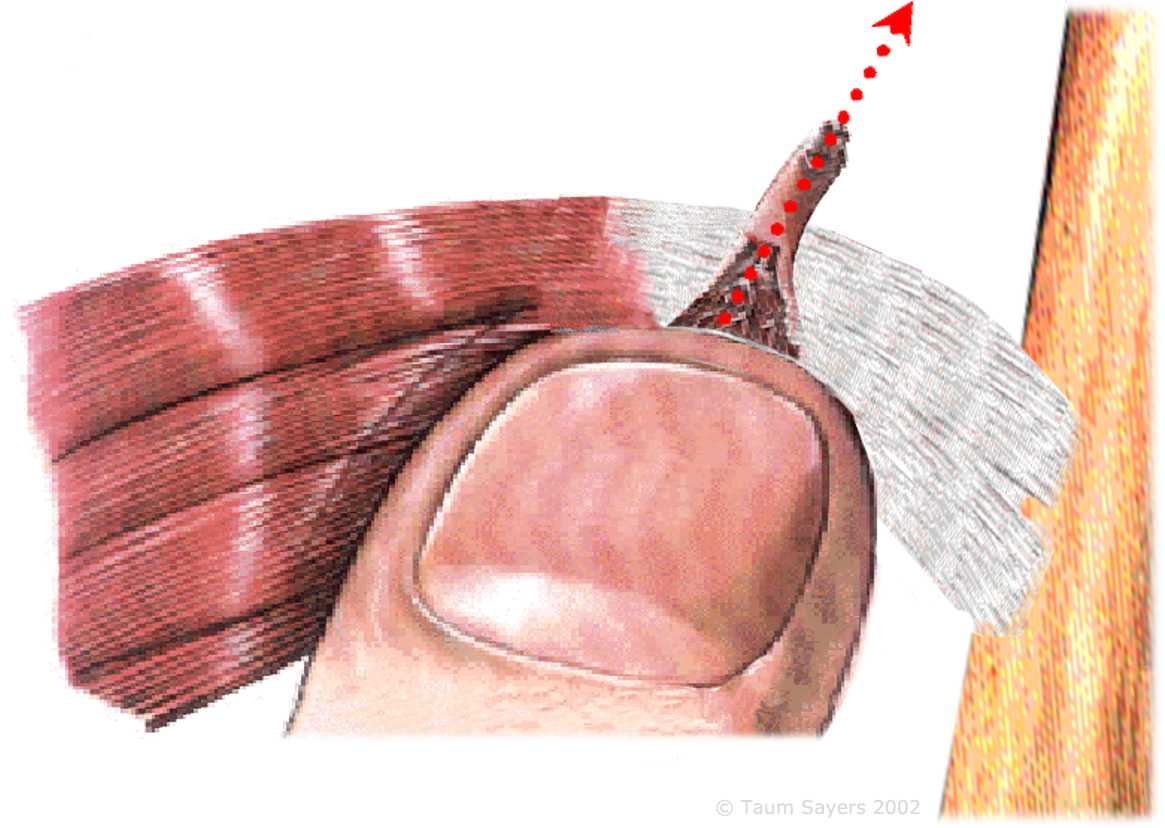

With thoracic tension, these two muscles, in addition to commonly being in a state of tension due to postural imbalances, appear to frequently distort in a lateral/inferior direction. The resultant tension is felt by the client most noticeably between the shoulder blades where these muscles attach. As part of any client's session, Lauren often suggested we massage the attachment points of a muscle before correcting its position. He explained this action would increase the blood flow to the muscle. After further anatomy investigation, it would appear to this author that massaging the attachments can also stimulate the properties within the Golgi Tendon Organ (GTO) (see GTO illustration), thus reducing the tension on the attachment points. Consider that within the neural/muscular mechanism, the stretch reflex regulates the length of skeletal muscle. The tendon reflex monitors the tension produced during a muscular contraction and prevents damage. The sensory receptors for this are the GTO's. They are located among the collagen fibers within the tendon near its muscular junction and serve to monitor the external tension on skeletal muscle. Their associated neuron is stimulated when the collagen fibers are under stress. They are more susceptible to activation during contraction than stretching, when the intention comes from within the muscle as opposed to an external force. Within the spinal cord, these neurons stimulate inhibitory interneurons that innervate motor neurons controlling the muscle. The greater the tension in the tendon, the greater the inhibitory effect on the motor neurons. Consequently, skeletal muscles are generally prevented from developing enough tension to damage their tendons. This serves as a built-in relief switch. (As an example of this protective mechanism, consider why you cannot hang onto a pull-up bar forever. At some point, the GT0 sends the message to your nervous system that the stress of holding on is reaching a point of muscular/tendinous damage. The brain responds by overriding your wish to continue hanging on and reprograms the muscle into a relaxed mode, thus weakening your grip, and you let go.)

It would appear that Lauren's technique also stimulates the mechanisms within the GTO to manually reduce a muscle's internal tension. This technique intends not so much to stretch the muscle as much as simulate stress within a particular muscle. By applying a specific cross-fiber massage, similar to pulling the string on a bow and arrow, this approach stimulates the natural properties within the neural/muscular mechanism to set off the GT0's response and persuade the muscle to relax. This technique is most successful when your intention is focused thru the surface tissue layers to your target fibers. I personally have a lot of admiration for bodyworkers who are very specific with their intent and their capacity to "see" with their fingers. An ongoing study of anatomy followed by practice in the field is an excellent way to nurture and refine these abilities. For example, you might find and palpate the two muscles discussed here on each of your next day's clients. I highly recommend that you begin with a clear intention and a light touch. Initiate by palpating the insertions of the iliocostalis thoracis and iliocostalis lumborum, acknowledging your client's feedback as to levels of discomfort. (I recommend an agreement so that should your pressure cross the line from therapeutic discomfort into pain, your client notify you with the code word 'ouch', and you will stop to assess the information. This serves two purposes…assisting you in your assessment with their feedback and allowing your client to relax further, knowing they have a say in this process.) This includes the attachments shared with the common tendon of the erector spinae. Though you probably will not be directly working on the GTO itself, the tendon is dense enough that your localized pressure can be transmitted to it to stimulate the desired response. This work is done without oil, allowing for precise manipulation of the tissue.

"Repositioning"

Part of the uniqueness of The Lauren Berry Method® is found in directly addressing and correcting soft tissue misplacement and distortion. In this situation, your direction of intention and pressure is medial/superior, focusing along the muscle belly.

A useful image is one of pushing or nudging dried strings of glue across glass with your

fingertips. Consider that the attachment points of the tendon represent a concentration of

force in one small area (the entire force of the muscle focuses tension on the bone through

the tendon at its attachment). Because of this, the tension/force (pounds per square inch)

at the attachment point is higher than at any point in the body of the muscle itself. There

are pain receptors at the bone surface (periosteum), which in turn can make the insertion

point very sensitive. It is thus helpful to expect these points to be tender and adjust your

pressure accordingly. Consider that you are not so much repositioning the fibers to an exact

position as much as you are introducing movement towards a balanced situation, thus reducing

adhesions and removing distortion. The muscle tissue, upon having the 'duct tape' removed,

will most often be able to nestle back to its optimal location. Note that one indication of

a misplaced and distorted muscle is when the fibers tactilely 'stand out' with that all too

familiar stringy/ropey feeling. Additionally, when muscle fibers are in their most

functional position, they usually blend back in with the surrounding fibers and 'tactily

disappear'.

A useful image is one of pushing or nudging dried strings of glue across glass with your

fingertips. Consider that the attachment points of the tendon represent a concentration of

force in one small area (the entire force of the muscle focuses tension on the bone through

the tendon at its attachment). Because of this, the tension/force (pounds per square inch)

at the attachment point is higher than at any point in the body of the muscle itself. There

are pain receptors at the bone surface (periosteum), which in turn can make the insertion

point very sensitive. It is thus helpful to expect these points to be tender and adjust your

pressure accordingly. Consider that you are not so much repositioning the fibers to an exact

position as much as you are introducing movement towards a balanced situation, thus reducing

adhesions and removing distortion. The muscle tissue, upon having the 'duct tape' removed,

will most often be able to nestle back to its optimal location. Note that one indication of

a misplaced and distorted muscle is when the fibers tactilely 'stand out' with that all too

familiar stringy/ropey feeling. Additionally, when muscle fibers are in their most

functional position, they usually blend back in with the surrounding fibers and 'tactily

disappear'.

The attachment points can serve as an important reference, so after addressing the surrounding regional tensions and distortions within the belly of the tender muscle, you can often return to a previously tender attachment to find it has relaxed. This can also serve to instill confidence in your client that there are benefits to the process.

By applying these techniques, you will have tapped some of the innate intelligence of the body, intentionally encouraging the muscle fiber to release chronic tension by overriding its protective state of contraction via the GTO, thus "reprogramming" it via the nervous system to relax. You will also have encouraged the muscle out of a distorted position and back towards a situation where it has a better opportunity to relax and repair.

Access and work on as many of the attachment points as you can and repeat the move on each. Be aware of scapula positioning so as not to strain the shoulder joint. Should a point be overly sensitive, work the surrounding region, including the body of that muscle and return for another pass; chances are it will be less sensitive the second time around. This qualifies as a deep tissue technique, so respect it as such. As you study these two muscles, consider how related muscle tension throughout the body can have the 'nose ring' effect up into the region between the shoulder blades. Get out your anatomy books and take a close look at the Iliocostalis Cervicis. Observe the attachment points near this area of concern. Take the above information and apply that to my observation that these fibers usually distort in a medial/inferior direction. Also, consider that if you have not addressed distortions in the lower back, your success rate will relate accordingly. Following these techniques with longitudinal oil work is a good way to bring this process to closure.

*Mirka Knaster, Discovering the Body's Wisdom (Bantam Books, 1996), p. 171

** The Institute of Integral Health, Inc.©, is a non-profit educational corporation located in Berkeley, CA, that continues to teach and certify practitioners in The Lauren Berry Method®.

Footnotes:

- James Cyriax, Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, 8th edition, 1982, Volume One, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, Bailliére Tindall, 24-28 Oval Road, London NW1 7DX.

- Palastanga, N.; Field F.; Soames R., Anatomy and Human Movement- Structure and Function, 2nd edition, 1994, Butterrworth-Heinemann Ltd., Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford, OX2 8DP.

- Licht, S.H., Massage, Manipulation and Traction, Fourth printing, 1976, Robert E Krieger Publishing Co. Inc., 645 New York Avenue, Huntington, New York 11743.

- Martini, F.H., Fundamentals of Anatomy and Physiology, 4th edition, 1998, Prentice Hall, Inc. Simon & Schuster / A Viacom Company, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458

- Alter, M.J., Science of Stretching, 1988, Human Kinetics Publishing, Box 5076, Champaign, Il 61820.

Taum Sayers is a certified Lauren Berry Method® practitioner, instructor, President of The Institute of Integral Health, Inc.©, and author who continues to practice and present workshops nationally and near his home in North Lake Tahoe, California. The foundation of his practice is primarily influenced by his apprenticeship with Lauren Berry Sr. RPT and his ongoing association with his fellow board members, teachers, and students within The Institute's ongoing educational programs.